There was recently a documentary on Channel 4 (in Britain) that highlighted an individual with Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP), a progressive bone disease in which the bodies natural repair mechanism causes fibrous tissues (including ligaments, tendons and muscles) to become ossified when damaged or hurt. Typically lumbered with the name Stone Man Syndrome, the genetic disease itself is thankfully very rare with a rough prevalence of around 1 in every 2 million people. A total of 700 cases have thus far been confirmed out of presumed 2500 cases worldwide at the current time. The disease is ultimately devastating for the individual affected as it can lead to full ossification of every joint in the body, whilst the ossification of the fibrous tissues is typically a very painful process. A full introduction to the disease can be found here on the emedicine website.

The program, entitled ‘The Human Mannequin‘, dealt with teenager Louise Wedderburn’s attempts to break into the fashion industry, despite her having this terrible disease. The information byline for the show asked if the ‘notoriously image conscious fashion industry (would) accept her?’. However, as the program progressed, it was clear to see that Louise had the tenacity necessary and had started to make clear progress towards her ideal career by gaining work placements at well recognised fashion magazines, and by starting to make her name known in the industry through her fighting spirit.

This program clearly was not about the disease itself, but about one person realising their dreams despite the disease. As such, there was minimal background information regarding the history of the disease or of the prognosis of Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. Instead this program helped to raise of the profile of a dynamic young individual who, despite having this disease, is determined to make the most of her life. The viewer was allowed access into what life is like for a person suffering this disease, both for the drawbacks and the numerous hospital visits, but also for the everyday glimpses of how you can still live your life and make a positive impact. I would wholeheartedly recommend watching the program if you have the chance.

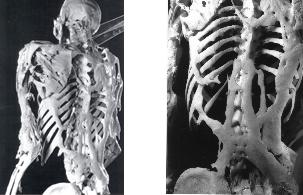

Perhaps the most famous sufferer of FOP is a person called Harry Eastlack (1933-1973), who bequeathed his skeleton to medical science whilst he was alive in the hope that his bones may one day help future researchers uncover a cure or help ease the pain of fellow sufferers. Dying just short of his 40th birthday through complications arising via FOP, Harry Eastlack had became entombed within his own skeleton towards the end of his life as every joint ossified and fused completely, leaving only his lips free to move.

A photo of Harry Eastlack’s back and ribcage, with evidence of excess bone growth and ossification of the muscles, tendons and ligaments (via IFOPA).

Today researchers and medical staff at the College of Physicians in Philadelphia and the Mutter Medical Museum use his skeleton to help test and compare lab results and learn and study about the effects of FOP via his remains; Harry’s skeleton is only one of the few existing skeletons in the world with FOP and provides a very important source of knowledge, both for the medical world and the general public.

There are no known instances of FOP disease in the archaeological record, likely because it is so rare and the fact that prehistoric/historic individuals would not have likely survived as long as individuals do today with the condition. However it is worth reading up on the disease just in case, and I would, once again, recommend watching the program. As so often in the fields of archaeology and human osteology, we only get to investigate the bones of the dead themselves, they cannot tell us directly their lives or suffering so we must, as osteoarchaeologists, beware of what the bones can tell us.

Further sites of interest:

- Bone, a Master of Elastic Strength, a New York Times piece on the architecture of bone.

- IFOPA is the International Fibrodysplasia Ossifcans Progressiva Association homepage with pages on funding, clinical research and help for families.

- IFOPA Facts Sheet, a fact sheet detailing the disease.

- Genetics Home Reference on FOP, a guide to understanding the genetics behind FOP.

- Medscape Reference on FOP, a page detailing the medical details of the disease including clinical presentation, pathophysiology, epidemiology, treatment, and prognosis.

Mr Bones, I like the way you humanise what you study (not that we can very well in the lithics world, but even there I think we can). We all must; make what we do of the past relevant now, make bonds between the past and our contemporary audiences, personal where needs be. Isn’t that what our ultimate goal is, beyond an “English Heritage signboard” over a monument? Cheers, S

Mr Carter, I couldn’t agree more! Thank you for taking the time to read the post.

Cheers,

David

Hi David,

Did you know that there are 3 FOP specimens at the Royal College of Surgeons of England in London? One is on display in the Wellcome Museum of Anatomy and Pathology (access to relevant fields only and by appointment). It’s pretty incredible to see if you ever get a chance.

Gretchen

Gretchen,

I have seen them myself! The Wellcome Museum of Anatomy and Pathology is a joy to behold and to revise in- I was lucky enough to visit it, and the Royal College of Surgeons, in May. Thank you for the information though! I hope you are well.

Regards,

David