Ever since the recent finale of series seven of the television series Game of Thrones (1), I’ve been revisiting the earlier episodes in order to remind myself of its intricate and myriad story-lines, alongside its cast of thousands of characters. Sometimes this can be a bit of a headache and a puzzle watching an episode, trying to tease out the relationships, experiences and personal histories of the characters before the scene ends and you are whizzed off elsewhere around Westeros (or the Dothraki Plain). This blog post may be about to do the same topic-wise, so prepare yourself!

New Lands, Old Fears

But Game of Thrones also offers a huge scope to visit different scenarios, locations and approaches, many of which are inspired from historical examples, such as the political intrigue of the War of the Roses (2.) in late medieval England and those of Imperial Rome. One of more important settings is the The Wall, a huge ice wall construction built thousands of years before the present setting of the series to separate the wild north from the kingdoms of the south. This structure is reminiscent of Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, which separated Roman-ruled Britannia to the more northern lands ruled by associated tribes of the Ancient Britons and Picts. In the television series though the northern lands are where ‘Wildings’ roam freely, loose tribes who live lifestyles akin to hunter-gatherers. It is also a place where rumours of the return of ‘White Walkers’ abound, human-like creatures said to be able to bring back the dead as animated revenants to haunt and slaughter the living.

Illustration of the Jewish mythological malicious spirit known as Dybbuk by Ephraim Moshe Lilien (1874-1925) in his Book of Job as it appeared in Die Bucher Der Bibel. The dybbuk is the dislocated soul of a dead person which goes on to possess another individual until it has accomplished its goal. Image from Wikipedia.

Before I get ahead of myself, the use of revenants in the Game of Thrones universe taps into a reoccurring and general unease in human cultures of the dead ‘coming’ back to life. Obvious parallels can be found and cited in the historical record from medieval Europe, particularly from Norway and England, but other cultural and religious examples include Chinese Jiangshi (‘hopping zombie’), the Jewish Dybbuk (a malicious possessing spirit), and the Malaysian and Indonesian Pocong (ghost of the soul of the deceased individual). The idea of the vampire, made famous by Bram Stoker’s Dracula novel of 1897 but present in many European traditions in one form or another in previous centuries, also fits this category. It would be fair to say that a fundamental feature of these concepts is the unease surrounding the death in general and the transition undertaken by the body as it undergoes the processes of decomposition.

The Old Bear

During one of the recent episode re-watches I came across the breakdown of the Night’s Watch, the politically unaffiliated band of brothers who guard the Wall against northern incursions and attacks. Safe from the internal politics of the Seven Kingdoms that make up Westeros, the Night’s Watch relies on volunteers or prisoners to help man the crumbling watch forts and man the walkways high atop the Wall. Unfortunately the members can prove to be a traitorous lot at times, particularly in times of hardship, de-funding and general building dilapidation as the kingdoms to south war among themselves.

The character I want to focus on briefly here is the Lord Commander Jeor Mormont (the Old Bear), an elderly individual who holds top spot in the Night’s Watch and tries to provide steady leadership during trying times. In series three, after an incursion into the frozen north ends badly following a somewhat terrifying encounter with the white walkers, the remaining men try to muster at a barely-defended longhouse (Craster’s Keep) before making for the safety of the Wall. Before this happens though trouble breaks out and ends in outright treason among a portion of the broken and bloodied men. The Lord Commander himself meets a bloody end at the hand of one of the mutineer’s blades and series three draws to a dramatic close.

The Lord Commander, though dead, still manages to make an appearance in series four. . .

Lord Commander Jeor Mormont, of the Night’s Watch, in better days at the Wall in Game of Thrones. Image credit: Game of Thrones Wiki.

. . . Alas not as a revenant, but as an inverted skull-cup!

In one of the early episodes to series four (it’s been too long since I saw it but I presume either episode one or two), we cut to one of the mutineers drinking wine out of the now defleshed skull of the former Lord Commander Mormont. I have to say, the skull-cup must have been well-plugged of any canals and foramen, let alone the magnum foramen!

If you are an adult check out the video below and see if you can tell, from an osteological standpoint, what the mutineer did incorrectly whilst handling a human skull (minus the drinking of a cold vintage from it)? Please note that the video below contains strong language, sexual violence and nudity (and yes, you have to click through to YouTube to view it).

If you had said grabbing the skull by the orbits (eye sockets), you would be quite correct!

Never grab a skull by the orbits or any other hole presented as you run the risk of damaging and breaking the delicate facial bones by doing so. Particularly at risk are the bones that help form the orbits and nasal aperture (nose hole), such as the lacrimals, nasals, zygomatics and sphenoid skeletal elements. There is also a bit of a give away that this is either a plastic model or cast, as in the first shot of the skull you can clearly see the shallow depth of the anterior nasal aperture. Apart from that though the model/cast looks quite good, relatively speaking.

A Mormont Skullduggery

There is of course another oddity here – why go to the hard effort of cutting off the calotte (skull cap) and use the base of the neurocranium (brain case part of the skull) and splanchocranium (facial part of the skull) as the drinking vessel, instead of using the calvaria (the skull without the facial bones or lower jaw)? Not only do you have the huge foramen magnum to plug, but also all of the intricate canals and foramen of the sphenoid bone, alongside the nasal aperture and orbits to prevent leakage.

It is, of course, for the shock factor and not for the practicality of drinking wine out of a skull. This is Game of Thrones after all. Still, it is impressive to see and one can imagine the (theoretical) hard work that has gone into plugging the anatomical gaps to make the butchered skull into a drinking vessel!

From Lord Commander to cup, the sorry fate of Jeor Mormont. Image courtesy of Youtube and HBO.

This thrilling north of the Wall strand in series three and four also reminded me of a few real-life archaeological parallels; from the Upper Palaeolithic post-mortem skull modification at Gough’s Cave, to the medieval treatment and disposal of the dead at Wharram Percy. So without further ado, let us take a look at the archaeological evidence and see what the individuals at Gough’s Cave did differently to the mutineers at Craster’s Keep.

Upper Palaeolithic Head Scratcher: Gough’s Cave

At the Upper Palaeolithic location of Gough’s Cave in Somerset, England, evidence for the post-mortem butchery and processing of human remains is present in the skeletal material recorded and excavated from the archaeolological site. The Magdalenian-period site dates to around 14,700 cal Before Present and is one of the few British Upper Palaeolithic archaeological sites to feature human skeletal remains at all. It is also the only site in the British Isles to feature the presence of directly-dated skull-cups (N=3), as documented in the two images below for location of butchery marks and the skull-cups themselves (Bello et al. 2017: 1).

Though Gough’s Cave is not the only Magdalenian culture to feature human skull-cups, as the French sites of Le Placard and Isturitz also have evidence for the post-mortem production of skull-cups, it is unique to feature both the production of skull-cups and the evidence for cannibalism together at one site. I’ve previously wrote a blog entry regarding the osteological and archaeological evidence for post-mortem manipulation of the bones, but it is worth just briefly going through it again here.

A selection of the skull elements from at least three individuals found at Gough’s Cave. Note the processed remains. Image credit: Natural History Museum.

The first hint that the skeletal remains were likely butchered was the find location and treatment of the skeletal elements. The remains of at least five individuals, including children, adolescents and adults, were co-mingled with butchered animal remains. The remains showed distinctive evidence for cut-marks and chopping, but more commonly for slicing and scraping (Stringer, et al 2011: 19). In total three skull-cups were identified from individuals of differing ages and all butchery marks were identified as ectocranial (outside of skull) in nature.

The archaeologists were able to identify the five-step method for producing the skull-cups as the following:

- The head was detached from the body shortly after death, cuts at the base of the skull and cervical vertebrae indicate this.

- The mandible (lower jawbone) was then removed, with evidence of percussion fractures on the teeth of both the mandible and maxilla (lower and upper jaws), where present.

- The major muscles of the skull were carefully removed, along with the soft facial tissues and organs.

- Cut marks then indicate scalping took place.

- Finally the facial and base of the cranium were carefully struck off and the edges chipped to provide smoother surfaces (Bello et al. 2011).

The main locations of reshaping of the human crania from Gough’s Cave IMage credit: Figure 8 in Bello et al. 2011.

Once created it appears that the skull-cups were used as liquid vessels rather than for anything else, although the reason for their production remains unknown. This function is similar to the fate of Lord Commander’s skull in the Game of Thrones television series, though we cannot know the reasons that drove the individuals who created the Gough’s Cave skull-cups in the first place. The possibility of funerary ritual could be floated, but this would be speculation. What is clear is that these skull-cups demanded careful preparation and processing to minimise damage. The 2011 PLoS ONE article by Bello et al., referenced in the bibliography below, is well worth a read for the full archaeological and osteological context.

Medieval Wonders: Wharram Percy

In more recent research on a skeletal assemblage from the deserted medieval village of Wharram Percy, North Yorkshire, dating to the 11th to 13th century AD, indicate a number of peri-mortem and post-mortem practices being carried out in distinct phases (Mays et al. 2017).

A study on the disarticulated assemblage of human skeletal remains (N=10), located within a pit-complex at the village, has uncovered evidence for peri-mortem breakage, burning and knife and chop marks. The archaeological context of the remains of the individuals indicated that this was a not discrete one-off episode but a part of a number of episodes within the residua of more than one event (Mays et al. 2017). A minimum of at least ten individuals are represented by the skeletal material within the study, ranging in age from 2-4 years old to >50 years at death.

The osteological analysis of the nature of the peri-mortem and post-mortem treatment of the remains indicated that there could have been motivating factors of starvation cannibalism or fear of revenant corpses driving the behaviour.

The modern view of the deserted medieval village of Wharram Percy. Photograph by Paul Allison, courtesy of Wikipedia.

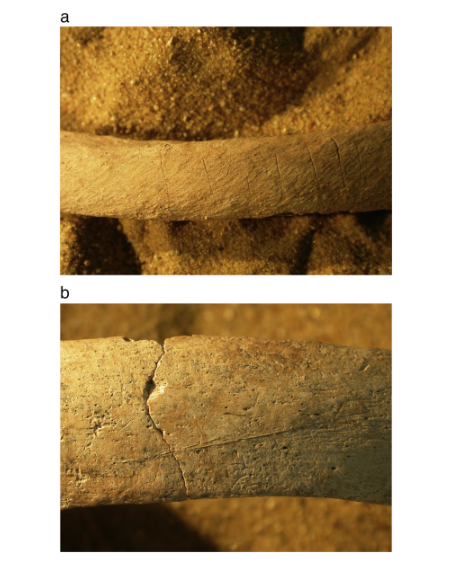

The examination of peri-mortem marks, largely sharp-force marks such as knife-marks, are largely confined to the upper body, along with evidence of long-bone peri-mortem breakage and low-temperature burning of a number of the bodies. The image below highlights a number of the knife-marks present on rib elements, but it was noted that cut marks could be found on various clavicles, humeri, mandibles, vertabrae and crania bases present, indicating there was a concentration on the head and neck area in order to separate the head from the vertebral column and inflict injuries upon a severed head. Meanwhile clavicular and upper rib cuts could be associated with dismemberment of corpses post-mortem. Unlike the cut marks and low-temperature burning, the evidence for long-bone peri-mortem breaking involved both the upper and lower limbs to a similar extent, although the presence of breaking was limited among the assemblage (Mays et al. 2017: 450).

The sequence of events, from the osteological material and archaeological contexts, suggests that the bodily mutilation preceded the burning, where both where in evidence (Mays et al. 2011: 449).

Evidence of parallel cut marks on the external surface of one rib fragment (a) from Wharram Percy, with (b) showing further cut marks on another rib fragment indicative of peri- and post-mortem funerary processing. Image credit Mays et al. (2011: 441).

Further strontium isotopic analysis of the dental enamel of sixteen molars, to test the range for geographic origin via local geology, were selected from the medieval cemetery population and the pit-complex assemblage. The testing revealed that nearly all individuals investigated all had local strontium values. Only one pit-complex individual, ‘mandible D’, had a non-local value which may have been from further afield (but only just, possibly). This analysis helped disprove the hypothesis that the pit-complex individuals, those with the knife-marks, and evidence for burning etc. came from a different geographic region than from the local area as compared to the control population of the cemetery group (Mays et al. 2017: 446).

In a 2017 University of Southampton press release for the article Simon Mays, a human skeletal biologist at Historic England known for his bioarchaeological research (such as Mays 1999), stated that:

The idea that the Wharram Percy bones are the remains of corpses burnt and dismembered to stop them walking from their graves seems to fit the evidence best. If we are right, then this is the first good archaeological evidence we have for this practice. It shows us a dark side of medieval beliefs and provides a graphic reminder of how different the medieval view of the world was from our own.

As the above and the Mays et al. 2017 research article below make clear, there is good evidence within the Wharram Percy pit-complex assemblage for the argument of starvation cannibalism and/or for treatment to combat the revenant dead, that is in order to stop a corpse from re-animating as per traditional mythology.

And yet there are arguments against both interpretations – the fact that there are barely any cut or knife-marks below the chest on the osteological material analysed, that there is a lack of pot-polish from boiling of the remains, or the fact that the revenant dead are usually male whereas the Wharram Percy pit-complex individuals include well represented females and non-adults.

Instead the investigators are careful with their interpretation and note the likelihood that the assemblage at this location, time and evidence point towards revenant activity rather than starvation cannibalism.

A Worthy End?

So there we have it, a very quick tour through the ages to see that although the Lord Commander Mormont suffered an inglorious end as a skull-cup, he was by no means the only one and he could not come back as a revenant. Although I picked fault with the method of his skull processing, we can see in the osteological and archaeological examples above that there are no set ways to process bodies during the peri- and post-mortem phases, therefore as bioarchaeologists or archaeologists it pays to investigate each avenue of evidence and see where it fits best within our current knowledge base.

Notes

(1.) Okay, I admit it – I started to write this post a while ago and I never quite finished it or got round to writing out a full draft. Game of Thrones, the HBO television series, has now finished with the somewhat rushed conclusion to series 8 airing in 2019. As of this blog post I am currently four volumes into the book series on which the television series is based, A Song of Ice and Fire by George R. R. Martin. It’s intriguing so far and I’m keen to see how it diverges from the television series.

(2.) The Wikipedia page on the War of the Roses has a fantastic family tree diagram with the affiliation of the kings, families and nobles of the various English civil wars that make up the 15th century conflict. It is well worth having a look and then trying to take it in the full page – it is not something I am particularly familiar with!

Further Information

- To read my 2011 post on the Upper Palaeolithic British site of Gough’s Cave, Somerset, which dates to 14,700 cal BP, click here. This is an incredible archaeological site which features the post-mortem processing (butchery and probable cannibalism) of human bodies, including the somewhat enigmatic skull-cups.

- Watch a wonderful movie on the Gough’s Cave skull-cups and learn more about the evidence via the Natural History Museum website.

- He may be the best knife fighter of Gin Alley but he sure as hell cannot hold a skull properly – watch the skull cup drinking scene that takes place north of the Wall at Craster’s Keep, courtesy of Youtube & HBO.

- Check out Kristina Killgrove’s Who Needs an Osteologist series, hosted on her blog Powered By Osteons. Read Howard Williams’s Archaeodeath blog which has a range of entries focusing on the way Game of Thrones use cremation in funerary rites throughout the TV series.

Bibliography

Bello, S. M. Parfitt, S. A. & Stringer, C. B. 2011. Earliest Directly Dated Skull-Cups. PLoS ONE. 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017026. (Open Access).

Mays, S. 1999. The Archaeology of Human Bones. Glasgow: Bell & Bain Ltd.

Mays, S., Fryer, R., Pike, A. W. G., Cooper, M. J. & Marshall, P. 2017. A Multidisciplinary Study of a Burnt and Mutilated Assemblage of Human Remains from a Deserted Mediaeval Village in England. Journal of Archaeological Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.02.023. (Open Access).

White, T. & Folkens, P. 2005. The Human Bone Manual. London: Elsevier Academic Press.

I’ve never seen Game of Thrones, but I am definitely interested in skull cups and revenants, so this was a fascinating post! I’ve been to Gough’s Cave, but somehow managed to forget there were skull cups involved.

Hey Jessica, glad to hear it! It goes a bit all over but I hope I made a good point or two. Ahh how was your visit?

Also sorry for the comments on your site yesterday! I thought WordPress had done something else with the format then. I decided to remove the ads from my blog as they were just pointless. And they made the skull-cups blog entry unreadable.

I hadn’t gotten any comments from you yesterday, so I checked my spam, and there they were! Looks like things were being sent straight there in addition to the buttons disappearing for you. I had an issue with my comments being sent straight to spam a while ago, and had to get it straightened out with WordPress. So annoying!

I went to Cheddar Gorge some years ago, well before I started blogging, but I definitely enjoyed it.

Ah absolutely fantastic! What did they give as the reason for that? I dislike WordPress more and more, plus the stats have really tanked now but I should probably also blog more. . .

Ahh nice, how was it?

I don’t think they gave a reason, just fixed it.

Cheddar Gorge is pretty great. We went to Wookey Hole on the same trip, which is not without its charms, but Cheddar Gorge was a bit less touristy, and you’re allowed to explore the caves on your own, though you can’t go very far in. They had one cave that was meant to be some kind of haunted quest, so it was full of skeletons and monsters and stuff. Obviously I enjoyed that, though it was pretty cheesy (pun intentional).

Ah fair does. WordPress never replied to my last message so it seems as though they have given up! Ahh now that sounds pretty good but understandable about the limitations. Also apologies for the delay in replying!